drumwordspokenbeat

Freeze Road

“Where is the yellow teapot?” I asked anyone who might be listening.

No one answered.

I stood on the black and white checkerboard linoleum floor in the kitchen of an old farmhouse that was a couple of miles out of town past the school of agriculture. I looked at the stovetop where there used to be a yellow teapot but now there was only yesterday’s soup.

“It’s coming in the mail on silver Hermes wings,” said a woman named Leona who lived in the farmhouse.

I did not understand her words but I got the meaning.

She spoke in poetry – words as materials — all meaning open to interpretation. At the moment I shared the farmhouse with Leona, a mad scientist, who grew weed in the bedroom, and a constant flow – students, travelers, vagabonds – who crossed the threshold, sat by the fireplace and pitched tents in the orchard. In the few months since I had arrived, many people had moved in and many people had moved out including a French literature major from New Orleans, a rock climber from the Midwest and a seed collector from Vermont. We had no furniture, we never used the heat, we stored our clothes and books in wooden apple crates. Our shared all possessions included a vintage sewing machine from the 1960s, a bentwood rocking chair from the barn and the yellow teapot. Leona hung a sign on the front door:

THIS PLACE DOES NOT EXIST

The path led me there. On my way out of the gathering, I followed the trail from the Fifth Dimension, past main circle, through welcome home and ‘A’ camp to the parking lot where my intuition told me I would find a ride to Ithaca. I ran into Leona on the path and it turned out that she was going the same way in a red car with a sunflower painted on the hood, a detail that brought the unwanted attention of customs officials at border crossings. Leona warned me not to bring any pot in the car.

“We’ll probably get pulled over,” she said in an accent that was nongeographical.

On the road back to Ithaca, Leona told me about a group of activists who were a marching band. In some ways they were like other marching bands — they went to parades, played brass instruments, practiced the high-step, the roll step and marched backwards, they had a drum corps, a tenor bass, a snare, clarinet, saxophone, oboe, trumpet, cowbells, cymbals and tambourines — banners and flags — but in some ways they were not like other marching bands. They marched for radical environmental change and the equality of all living beings. They marched against rampant capitalism and corporate greed. They had confrontational ways to get the message out. As Leona said, “we play loud.” The band marched with a banner:

STOP CRIMES AGAINST NATURE BY ANY MEANS NECESSARY

STOP GLOBAL WARMING, DEFORESTATION, AIR POLLUTION, WATER POLLUTION, NUCLEAR POWER, CLEAR-CUTTING, HABITAT DESTRUCTION, ANIMAL EXTINCTION, RADIOACTIVE WASTE, TOXIC LANDFILLS, OZONE DEPLETION, COAL MINING, DRILLING FOR OIL, OIL SPILLS, MERCURY POISONING, CHEMICAL DUMPING AND ALL OTHER ENVIRONMENTAL INJUSTICE!

“We’re going to protest a toxic dump site on the Hudson,” Leona said. “We built a boat out of used plastic bottles that we will float down the river in protest. We named it the Junk. As it floats away the band will play a funeral march.” She invited me to join.

One constant thing about travel is change. Now I am sailing a junk down the Hudson. A minute ago, I was looking for a ride to Ithaca.

“How can I help the cause?”

“Do you play an instrument?”

The marching band played anything that made noise – washboard, shakers, buckets — Leona played the drum, tambourine and she waved flags – each one printed with an image — skull and crossbones, radioactive symbol, biohazard sign.

As she talked about the junk, I caught a vision of Leona tossing a flag into the air, silk fabric rippling through space, creating the illusion that it was moving by itself. The fabric sounded like a sail snapping in the wind. She caught the flag and tossed it again – a single toss, a double toss, a parachute toss, a helicopter toss. The flag said:

RESIST

No one turned on the heat in the farmhouse on Freeze Road and we rarely used electricity. We conserved resources, preferred candlelight and couldn’t pay the bill. We had a touch tone phone that plugged into the wall with a coiled cord to the receiver. When I moved into the farmhouse after camping all summer, it felt unnecessary to have indoor plumbing and a stove. Central heat was extravagant. We unplugged the washing machine and the dishwasher. I slept in a nook at the top of the stairs that was partitioned off from the rest of the house by a curtain that was more symbol than screen. The farmhouse was an unintentional community, cooperative and commune where everything belonged to everyone in theory. Before its current incarnation as a free house, the farmhouse was occupied by an elderly woman who we knew from the spirit realm as Ms. Frances. She lived in the house that was built by her grandfather for the entirety of her long life. We always called the house Ms. Frances’ house because it felt more hers than ours. It was certainly more Ms. Frances’ than the current legal owner, a landlord who bought it at auction after Ms. Frances’ untimely death at the age of one hundred and eight. The new landlord, who was known as a slumlord, dumped her possessions in an old barn on the property and rented out the house unfurnished. We found a lifetime of belongings in the barn and brought them back to the house for another incarnation – rickety antique furniture, fraying handstitched quilts and the yellow teapot.

When the seed collector and I visited the barn, we rolled the hand-hewn wooden doors apart with great effort because of the immensity and the number of things piled up inside. We opened the doors wide enough to allow a beam of sunlight to illuminate a mountain of worldly goods — haphazardly overturned chairs, a red velvet couch, dozens of boxes, stacks of books, piles of clothes. This recent avalanche was only the first layer. The next section of household sediment was stored in a more organized manner. When my eyes adjusted to the cavernous space, I could see the depth of the sea of possessions – old fashioned furniture, rolled up rag rugs, upholstered chairs, boxes of newspapers, vintage glass bottles, cast iron pots and pans. The next layer of things was older and dustier — apple crates, mason jars, old National Geographics, a length of fence, wooden ladders, rusty rakes, bicycle wheels, coiled ropes, empty jugs, woven baskets, farm tools, an axe, a pulley, a wheelbarrow — a pair of cane-seat chairs hung on the wall waiting to be fixed.

I noticed a loft with a diamond shaped window under the eaves. “I wonder what’s up there?”

The seed collector said, “treasure”.

I climbed over the mountain of debris to a creaky ladder that led to the loft where I discovered a collection of objects that was even older and dustier – cracked leather boots, pale pink silk underwear, letters written in formal script on yellowed paper, a black and white photograph of a young soldier standing under the Arc de Triomphe, a woman in a bathing suit posing on the beach. An unintended memoir of generations. We gathered items to bring back to the farmhouse – a blue tin pitcher, a box of mason jars, a calendar from a long-forgotten year. We only took what we could reuse.

On the way out of the barn, I turned over an apple crate and jumped when I saw a pair of yellow-green eyes looking back at me. It was a dusty black cat, who I carried to the farmhouse.

“Where did you find the cat?” The wild haired trumpet player who lived in a tent in the meadow behind the orchard asked when he saw me feeding the cat in the kitchen.

“He was a barn cat but now he’s a house cat.” I touched the feathery fur between the cat’s ears. “Forever and always a free-roaming cat.”

“What’s his name?”

“Spooky.”

The wild haired trumpet player crossed the checkerboard floor of the kitchen to the screened-in mudroom and out the back door. All cats welcome at Ms. Frances’ house.

If you followed the trumpet player across the kitchen and through the mudroom past buckets of black walnut hulls soaking in water to make dye and out the backdoor, you would reach an overgrown garden with narrow footpaths like a maze. One of the paths dead-ended at a large cedar tree, another led to a trellis covered in wild grapevine, one led to a wrought iron bench and a birdbath under an arbor — remnants of the days when the garden was tended by Ms. Frances and her ancestors. If you took the path under the arbor by the pear tree, you would pass the old barn on your right and come to an apple orchard planted by Ms. Frances’ grandfather. The trees had thick gnarled trunks and branches weighed down by apples in shapes not found on supermarket shelves. If you kept walking, you would come to a gently sloping meadow of grasses and wildflowers where the trumpet player’s blue tent was set up near a stand of trees. If you went all the way to the bottom of the meadow, you would find a small creek flowing north to south over ancient shale, sandstone and silt, carving natural swimming holes with enough room for one person to submerge.

I held my breath and went under.

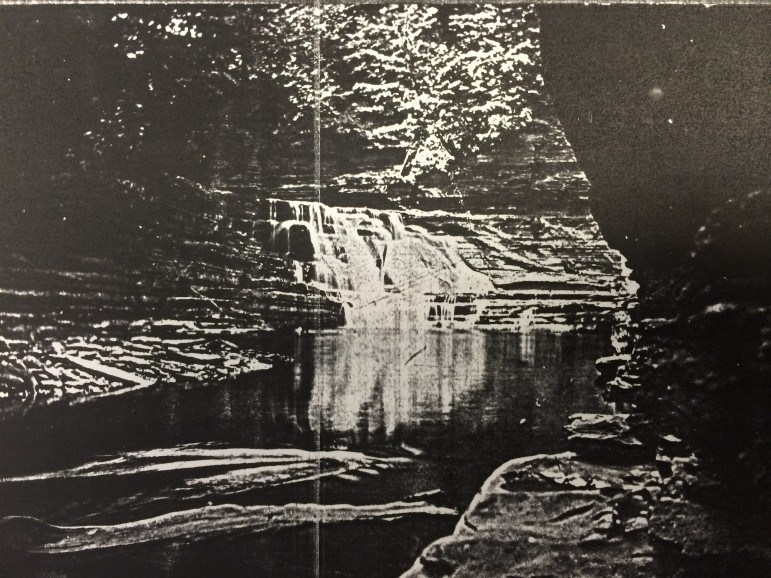

Water rushing over rocks, running downstream, gathering speed, gaining momentum, flowing through steep canyon walls, crashing down waterfalls. Everything in Ithaca flows to the lake.

I followed the water on my way to my shift at the ABC Café. I rode a bike that I found leaning against the side of the house. When it rained, I stood on the road in front of the farmhouse and held out my thumb. I was on the right side of the road — everything flowed with the water.

One Sunday morning in the middle of winter, I stood on the side of the road with my thumb out waiting for someone to stop and pick me up. The temperature was below zero – everyone who did not have to be out stayed indoors — a few cars passed intermittently. Freeze Road was frozen. After a longer than usual wait, a car pulled to the side of the road. The driver was a serious young man with short hair and a button-down shirt but he unlocked the passenger-side door and moved his messenger bag from the seat to the floor. “Are you hitchhiking?”

“This is the sign,” I held up my thumb.

My fingertips were numb in wool gloves. I rubbed my hands together in front of the heat vent to warm up, “It’s freezing out there.”

“Isn’t hitchhiking dangerous for a girl?”

“Did you just say ‘for a girl’?”

I said, “stop the car.”

“What? Why?”

“That’s as bad as ‘boys will be boys’.”

“Wait! I didn’t mean anything.”

“Hitchhiking is an equal rights opportunity,” I told him, “in fact women get more rides.”

“I’ll take you anywhere you want to go.”

It was too cold to get out.

Once on a road trip, Moon and I picked up a hitchhiker on the road in upstate New York. It was a man wearing a suit that did not fit with an unpredictable look in his eye. He sat in the backseat and laughed to himself – we kept our eyes on him in the rearview mirror. At one point he reached into the breast pocket of his jacket and pulled out a switchblade that turned out to be a hair comb. We invented a reason to drop him off. A few miles later, we saw a sign:

STATE PRISION

DO NOT PICK UP HITCHHIKERS

“Are you an escaped con?” I asked the serious man to make conversation.

“An escaped con? Of course not. I’m a law student,” he said, “what I meant to say was, isn’t dangerous for you to hitchhike by yourself?

“You never know what you can do until you try.”

“Do you live nearby?” I trusted him completely.

“I live in the farmhouse where you picked me up.”

“That place looks haunted especially the old barn.” The law student’s car coasted down the hill past the arboretum, the plantations and the orchards.

“It’s haunted by the spirits of homeless cats.”

“You may need my help someday.”

“You may need my help someday,” I echoed.

The law student pulled up in front of the ABC café.

The Buddhist monks dressed in saffron robes from the Namgyal monastery were eating brunch in the window.

“Thanks for the ride!” I ran inside.

I tied an apron around my waist.

The cook yelled, “orders up!”

The collective tip jar said:

IF YOU FEAR CHANGE LEAVE IT HERE

I contributed my paychecks to Ms. Frances’ house. We brought a typewriter to the Commons and wrote letters for spare change. We paid the slumlord each month. One short-term resident bought a fifty-pound sack of cornmeal, which played a role in every meal, another roommate made dandelion wine and sticky fingers with slippery elm and arrowroot, a houseguest from Vermont mopped the floors, someone paid rent in Ithaca Hours.*

*NOTE: Ithaca Hours was an alternative local currency printed on watermarked cattail paper or handmade hemp — bills featured images of women, Native Americans, waterfalls and animals of the bioregion. One Ithaca Hour equaled $10.

Leona, the mad scientist, a French lit student who drove a royal blue hoopty, a philosophy student who drank tea, played records, climbed tall structures and dangled upside down from his knees and a woman known as Maya Atlas who started fires with a bow drill. One of members of the marching band was wanted for destroying public property:

BOMB THE GOVERNMENT

FUCK UP THE POLICE

CAPITALISM KILLS

We had three cats in the house and then they had more cats and then we lost count. We had a bunch of dogs passing through. Ms. Frances’ house filled with people. More came and pitched tents in the meadow. A naturalist built a dome-shaped shelter called a wickiup out of bark. He did not use electricity, which was good because the mad scientist who was a brilliant student of botany used so much in his grow room. Pot plants occupied every inch of floor space except for a rectangle the size of an inflatable camping mat and sleeping bag.

The botanist owned the only computer in the house and because it was a free house, everyone used it in the artificial sunshine of 1000-watt grow lights with green cannabis sativa leaves blowing in the fan-generated breeze.

One spring day when I was writing a paper in the grow room, I heard the front door slam open with a bang. Oh no, I thought, not again. I heard the sound of heavy footsteps on the stairs.

“Turn off that motherfucking noise right now,” the botanist shouted, “my plants don’t listen to rap!”

He stormed into the grow room and hit the button that said:

STOP

I knew facts were the only way to reason with him. “Music makes plants happy.”

“My plants only listen to classical — to stimulate growth.”

“Plants listen to whatever music you put on for them,” I gathered papers and books.

“Get out of the grow room!” The botanist looked like he was about to spontaneously combust.

“You can’t get kicked out of a free house,” I reminded him. He slammed the door. You have to pick your battles. The marching band floated the junk down the Hudson and made the local news with a clip of Leona waving the flag with the radioactive symbol while the band played a clangy slow-motion version of Chopin’s funeral march.

The marching band planned their next action. There was a small grove of old-growth trees — a near-impossible find on the East Coast — thirty acres of hemlock, hickory, beech, maple, cherry and the hard-to-find yellow oak – slated to be clear-cut. The stand was one of the last examples of what East Coast forests looked like before European settlers arrived and began to cut down the ancient trees. The trees grew to be hundreds of feet tall with expansive canopies that supported whole ecosystems of plants and animals. This is how the land appeared to the Haudenosaunee (people of the longhouse).

The marching band voted unanimously to enter the grove in the middle of the night and take up residency in the trees. They pitched tents and hung hammocks in the branches. They brought instruments: a banjo, a washboard, a jug. They wore bandanas over their faces for anonymity but you could see their souls through their eyes. When a reporter came to cover the story, they chanted, “no compromise in defense of mother earth!”

“Stop crime against nature by any means necessary!”

When the police arrived to break up the protest, they discovered that the tree-sitters had used bike chains to lock themselves and their instruments to the trees. Leona climbed to a high branch and dropped a banner that said:

TREE OF LIFE

In the end the trees were saved — you can visit them if you can find them — the grove is unmarked from the road. From Ms. Frances’ house, take the road south out of town. The foundation of an old stone barn marks the beginning of the trail. Follow the trail down a hill through a meadow and turn right at the fork in the road. You will notice the trees grow taller and the canopy reach higher as you enter the ancient forest. The trees were saved but other things were not. The black walnut dye was poured out of the buckets in the mud room onto the earth staining it with tannins. The misshapen apples on the trees in the orchard dropped to the ground before the first snow and the branches were covered in apple blossoms in the spring. More travelers came to the house – some stayed, some moved on — everyone was welcome.

Leona hung a sign on the front door:

THIS PLACE DOES NOT EXIST

And maybe that is why we kept losing things.

“Where is the yellow teapot?” I asked.

“Has anyone seen spooky cat?”

by Lea Lion